This week marks the Centennial of two tragic fires in New York State -- one which resulted in great loss of life, and one which destroyed or damaged irreplaceable documents about New York State's history.

March 25, 1911: You may have heard of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, which broke out suddenly just before quitting time in a factory on the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors of the Asch Building at Washington Square Place in Manhattan. The factory employed nearly six hundred workers, mostly young women, who cut and sewed tailored blouses or "shirtwaists" so popular in the Edwardian era.

A commemorative exhibit in the Concourse of the Empire State Plaza in downtown Albany, New York, displays photographs and newspaper stories from that day, citing the following details: The fire broke out at the end of the work day; ten minutes more and all the workers would have been out. But emergency doors were kept bolted, "to safeguard employers from the loss of goods by the departure of workers through fire exits instead of elevators." The flimsy fire escapes collapsed under the weight of so many people trying to escape, plunging many to their deaths.

Firefighters' ladders only reached as far as the sixth floor. The workers had little choice: jump or be burned. It was all over in less than 30 minutes. When firefighters arrived, the street was already littered with bodies. In all, 146 workers, mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women, died.

The factory owners were not held accountable even to the standards of the day: fire hoses in the building were not connected, equipment blocked access to ladders and other precautions were ignored.

The public outrage at this avoidable tragedy led to many measures that we take for granted today. Labor unions and other civic groups demanded steps that could protect against such tragedies, and thus the New York State legislature took immediate action and passed extensive safety laws.

A centennial commemoration at the New York State Museum on Friday, March 25, 2011 included remarks by several local dignitaries; a reading of the words of Frances Perkins, the first female U.S. Secretary of Labor, who witnessed the tragedy and made it her life's work to defend the rights of workers; and a reading of the names of the 146 victims of the fire.

As a witness to the tragedy, Perkins wrote, "People who had their clothes afire would jump. It was a most horrid spectacle. Even when they got the nets up, the nets didn't hold in a jump from that height. There was no place to go. The fire was between them and any means of exit." Later, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor, Perkins became a dynamic defender of workers' rights, human rights, and humane health and safety standards.

Additional documents and photographs pertaining to the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire can be found on the Web site of the New York State Archives.

March 29, 1911: Less than a week after the tragedy in New York City, while making his rounds shortly after midnight, the night watchman at the Capitol building in Albany discovered a small fire in the Assembly library on the third floor of the building. At this time, the Capitol was also home to the State Library, the Museum, and the State Library School. Due to the profusion of papers and books in the overcrowded library, the fire spread quickly, gutting the three floors occupied by the State Library with unprecedented speed.

A recent book by librarians Paul Mercer and Vicki Weiss recounts the story of the fire and its aftermath, drawing upon documents in the New York State Archives. Picture if you can, Albany's ten horse-drawn steamers and three horse-drawn ladder trucks racing to the flaming building in the dead of night, aiming their puny hoses on the raging flames. The pine bookshelves collapsed, floors and even part of the roof collapsed, and the heat of the fire even twisted iron girders and ate away at granite columns. When it was over, in some parts of the building that survived, the rubble of collapsed floors and walls was 40 feet deep.

Librarians risked their lives to salvage what precious documents and artifacts they could, most notably Joseph Gavit, who had begun his library career at age 19 upon graduation from high school in 1896 and worked as a librarian at the State Library for 50 years, retiring in 1946. Although over a half million books and manuscripts were lost, under Gavit's direction, workers were able to save many precious records dating back to the founding of Rensselaerswijk in the 17th century, as well as the original manuscript of President George Washington's farewell address, President Abraham Lincoln's original Emancipation Proclamation and the original copies of the New York State Constitution. Other documents were only sodden masses of parchment. But luckily, contrary to the loss of life earlier that week in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, there was only one death at the Capitol that night -- Samuel J. Abbott, the elderly watchman who discovered the fire.

In evoking the world in which our grandparents came of age, it is useful to ponder how events in that era at the beginning of the 20th century shaped our own. We have already noted above how following the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, legislation was enacted to try to prevent such a tragedy and to protect the rights of workers. It is likely that New York's legislators acted with haste after the fire that ravaged their own quarters; while restoration of the Capitol was undertaken, they had to take up temporary residence in Albany's City Hall across the street.

The Great Capitol Fire also resonates with our time. Eventually work began to restore damaged documents and rebuild the State Library collections, as well as to restore the building itself. Although at first, remnants of the library and archive documents were housed in a number of locations around Albany, in 1912 the Library moved into new quarters at the State Education Building across from the Capitol, which was still under construction at the time of the fire.

Although it would take a decade before the state archivist A.J.F. van Laer would resume his work of translating Albany's Dutch colonial records, the restoration and translation work goes on to this day. The New Netherland Institute, led by Dr. Charles Gehring, is now housed in the current New York State Library on the seventh floor of the Cultural Education Center. And thus you can view 21st century digital images of the 17th century Dutch documents scorched by the 20th century fire.

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

Thursday, March 24, 2011

"The Giechelaars"

Whenever relatives from Holland came to visit, my mother and her siblings would be delighted to entertain them -- and delighted to hear once more the language they remembered from their childhoods.

Out would come the best china teacups and silver only used on special occasions; into the oven would go the Dutch sand cookies or apple cake to accompany the fragrant tea. Sometimes other Dutch acquaintances or relatives who had emigrated to Canada would come to join the group around the dining room table.

And then, in counterpoint to the click of spoon against saucer, the giggling would start. The family gatherings were always full of lively conversation and hearty laughter. In fact, if you laughed too much, you were a "giechelaar," from the verb giechelen, to giggle.

The first relative I remember coming to visit from the Netherlands, probably around 1961, was Grandma VandenBergh's younger brother Jasper, my Mom's "Oom Jas," who always regaled the group with amusing tales of family doings on the other side of the Atlantic. He did not speak much English, but that did not stop him from enjoying his visit to America. On one of his walks around the neighborhood, he met an Italian immigrant who didn't speak English either, and the two conversed with gestures and broken English.

Relatives invariably brought gifts from the Netherlands too -- dainty silver teaspoons (Dutch cousins were always surprised at how big American teaspoons were!); recordings of Dutch patriotic songs, or a book of piano arrangements of Dutch songs; and another time a fancy wind-up clock that chimed every half hour.

But the best gift was the sense of conviviality and shared heritage with the cousins from across the sea.

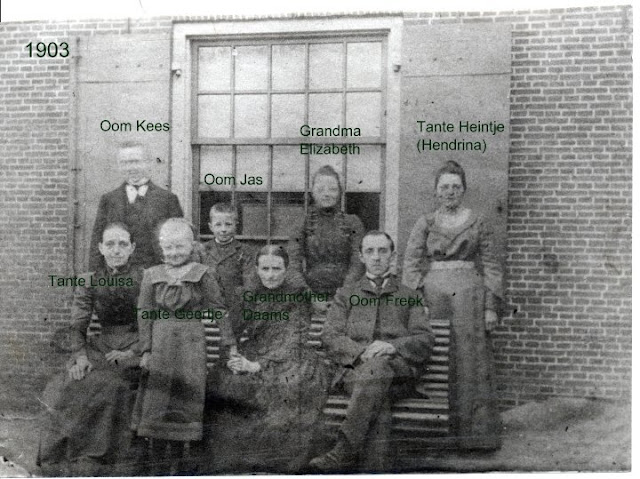

In the family archives is a photo that dates from 1903, showing my great-grandmother Geertje Daams (nee Vonk), who was born in 1851, with her children grouped around her. Great-grandfather Jasper Daams (born in 1836) had passed away four years before the family portrait was taken. See if you can identify Grandma VandenBergh and Oom Jas:

The answer is at the end of this post. But first, this week's recipe:

The cookies shared at family tea parties were sometimes stroopwafels (a round waffle-type cookie with a syrup filling, that would become deliciously warm when placed over a cup of hot tea), or speculaas (spice cookies) brought from Holland, or home-baked Dutch sand cookies from a recipe share by a family friend:

These are delicious buttery sugar cookies, maybe called sand cookies because they turn out to be the color of sand when baked. In trying out this recipe, I attempted to reduce the fat content by substituting butter-flavored baking sticks, which the package claimed to contain 50 percent less saturated fat than butter. This was not entirely successful, since the dough did not become as firm as it should have upon being refrigerated overnight. Thus the "sausage" of dough was a little bit hard to work with the next day.

And when they came out of the oven, the cookies were a little hard to remove from the cookie pan. I recommend using half butter and half margarine, which would still have less cholesterol than all butter, but probably make the dough a better consistency:

Even so, they tasted almost as good as I remember from the tea parties of my youth. Like Proust's madeleine cookies, when I dipped them in my tea, the flavor conjured up memories of the tea parties of my youth.

And now, as promised the Daams family who's who:

Thanks to Margriet W. for scanning and labeling this old photo!

Out would come the best china teacups and silver only used on special occasions; into the oven would go the Dutch sand cookies or apple cake to accompany the fragrant tea. Sometimes other Dutch acquaintances or relatives who had emigrated to Canada would come to join the group around the dining room table.

|

| Tea Party chez Aunt Grace: l. to r. Uncle Norman, Aunt Grace, ?, ?, Aunt Louisa, Oom Jas |

And then, in counterpoint to the click of spoon against saucer, the giggling would start. The family gatherings were always full of lively conversation and hearty laughter. In fact, if you laughed too much, you were a "giechelaar," from the verb giechelen, to giggle.

The first relative I remember coming to visit from the Netherlands, probably around 1961, was Grandma VandenBergh's younger brother Jasper, my Mom's "Oom Jas," who always regaled the group with amusing tales of family doings on the other side of the Atlantic. He did not speak much English, but that did not stop him from enjoying his visit to America. On one of his walks around the neighborhood, he met an Italian immigrant who didn't speak English either, and the two conversed with gestures and broken English.

|

| Tea Party chez Aunt Louisa: l. to r. Uncle Jake, Oom Jas, Aunt Connie |

But the best gift was the sense of conviviality and shared heritage with the cousins from across the sea.

In the family archives is a photo that dates from 1903, showing my great-grandmother Geertje Daams (nee Vonk), who was born in 1851, with her children grouped around her. Great-grandfather Jasper Daams (born in 1836) had passed away four years before the family portrait was taken. See if you can identify Grandma VandenBergh and Oom Jas:

|

| Daams family portrait 1903 |

The answer is at the end of this post. But first, this week's recipe:

The cookies shared at family tea parties were sometimes stroopwafels (a round waffle-type cookie with a syrup filling, that would become deliciously warm when placed over a cup of hot tea), or speculaas (spice cookies) brought from Holland, or home-baked Dutch sand cookies from a recipe share by a family friend:

|

| Mom's handwritten copy of cookie recipe |

These are delicious buttery sugar cookies, maybe called sand cookies because they turn out to be the color of sand when baked. In trying out this recipe, I attempted to reduce the fat content by substituting butter-flavored baking sticks, which the package claimed to contain 50 percent less saturated fat than butter. This was not entirely successful, since the dough did not become as firm as it should have upon being refrigerated overnight. Thus the "sausage" of dough was a little bit hard to work with the next day.

And when they came out of the oven, the cookies were a little hard to remove from the cookie pan. I recommend using half butter and half margarine, which would still have less cholesterol than all butter, but probably make the dough a better consistency:

|

| Just out of the oven! |

|

| Tea and sand cookies |

And now, as promised the Daams family who's who:

|

| Daams photo with names |

Thanks to Margriet W. for scanning and labeling this old photo!

Sunday, March 20, 2011

Spring Scenes in Loosdrecht

First day of Spring! In Upstate New York, the days are getting longer and brighter, and snow is melting (not fast enough), leaving the brown earth exposed, still marred by patches of dirty gray snow. It's "unoogelijk" -- unsightly -- as my mother would say. But soon the crocuses will poke up from the thawing soil, and other little green things will begin to sprout as well.

In the Dutch countryside too, it is early spring, and tulip bulbs that have lain dormant all winter will soon wake up. A hundred years ago this month in Loosdrecht, my grandparents were probably already planning their wedding. They would marry in two months time.

The photos below, taken fifty years later by Elisabeth's nephew Jasper, show the villages of Loosdrecht and s'Graveland, respectively the hometowns of Elisabeth Daams and Barend VandenBerg, as they appeared around 1960. It is interesting to speculate how much these scenes have changed (or not) over the years.

Loosdrecht actually consists of two small villages, Old and New Loosdrecht. Today it is a vacation destination for those who like to sail on the several interconnected lakes in the area. The lakes originated in the 16th century as a result of digging out peat bogs. There are also several canals that connect the village with the neighboring town of s'Graveland and with the city of Hilversum to the east.

Of course, there is also a road between the two towns. I picture Elisabeth and Barend riding bicycles along the road, perhaps meeting halfway in between:

Through the wonders of the Internet, I can tell you that as I write this, it is 10 degrees Celsius (50 F.) and sunny in Loosdrecht. Check it out for yourself right here. (Of course, when you click on the link, the weather may be different!) It is muddy along the marsh in spring, but this photo looks like it could have inspired Van Gogh:

A hundred years ago the Daams family owned a blacksmith's shop, and the family resided next door to the shop. Elisabeth was born in the family home on March 29, 1886:

Here the s'Graveland Canal joins the Hilversum Vreeland Canal. The scene is reminiscent of landscapes painted by the old Dutch masters:

And here the "road less traveled" leads to an estate where my great-grandfather worked as a gardener.The terrain looks much like the countryside around my own hometown at this time of the year:

The tour ends here, as the road leads into the forest where spring will soon turn the countryside green and fragrant with blossoms. One last patch of snow still remains just in front of the gate.

Many thanks to Margriet W. for digitizing these fifty year old slides.

Tot ziens! Good-bye for now!

|

| Mill in Westbroek |

The photos below, taken fifty years later by Elisabeth's nephew Jasper, show the villages of Loosdrecht and s'Graveland, respectively the hometowns of Elisabeth Daams and Barend VandenBerg, as they appeared around 1960. It is interesting to speculate how much these scenes have changed (or not) over the years.

|

| Canal in Loosdrecht |

Of course, there is also a road between the two towns. I picture Elisabeth and Barend riding bicycles along the road, perhaps meeting halfway in between:

| |||||

| The road between s'Graveland and Loosdrecht |

Through the wonders of the Internet, I can tell you that as I write this, it is 10 degrees Celsius (50 F.) and sunny in Loosdrecht. Check it out for yourself right here. (Of course, when you click on the link, the weather may be different!) It is muddy along the marsh in spring, but this photo looks like it could have inspired Van Gogh:

|

| A marsh in Loosdrecht |

A hundred years ago the Daams family owned a blacksmith's shop, and the family resided next door to the shop. Elisabeth was born in the family home on March 29, 1886:

|

| The old Daams smithy circa 1960 |

The sign over the building reads, "plumbing supplies, stoves, oil burners."

Heading north from Loosdrecht, you might happen upon the following scenes:

|

| S'Graveland Canal |

|

| Old house along the canal |

|

| Rear of houses along the canal |

In s'Graveland there is a Dutch Reformed Church, where my great-grandfather was organist for 40 years:

|

| Reformed Church and parsonage |

You can see the church tower behind the parsonage.

Here the s'Graveland Canal joins the Hilversum Vreeland Canal. The scene is reminiscent of landscapes painted by the old Dutch masters:

|

| Canal scene: s'Graveland |

And here the "road less traveled" leads to an estate where my great-grandfather worked as a gardener.The terrain looks much like the countryside around my own hometown at this time of the year:

| ||||

| Country lane near s'Graveland |

Many thanks to Margriet W. for digitizing these fifty year old slides.

Tot ziens! Good-bye for now!

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Potatoes, Part II

The Dutch word for potato is aardappel, which means literally, "earth apple." It corresponds to the French pomme de terre. The English word potato derives from Quechua and Taino words for respectively, white and sweet potatoes.

Potatoes have long been a staple of the Dutch diet. Every art student can identify the famous painting of a Dutch peasant family sharing their evening meal of potatoes. Even today, the Netherlands is the leading world producer of potatoes, for local consumption and export, due to its longstanding agricultural tradition, good soils, and temperate climate.

According to the Netherlands Potato Consultative Foundation, about a quarter of all arable land in the Netherlands is used for growing potatoes; and some 20 percent of this (35,000 to 40,000 hectares) is used for the production of seed potatoes. The majority of the seed crop is exported to over 80 countries around the world. This amounts to an annual export of some 700,000 metric tons of seed potatoes.

The Foundation conducts ongoing research to develop new varieties of potatoes by crossing two strains that exhibit desirable characteristics. The qualities sought by growers include resistance to disease in order to reduce the need for pesticides, the amount of water required to irrigate the crop, and the length of time the harvested crop can be stored.

Every year, the researchers produce over 1.5 million seedlings, but only three or four possible new varieties will be grown for mass production. Once a viable new variety is developed, it has to be quickly multiplied. Large-scale propagation will turn the myriad small plants into hundreds of thousands of salable products, which amount to about 70 percent of the registered world trade in certified seed potatoes.

Based on all of the above, you might suppose that the Dutch have also figured out a variety of ways to prepare potatoes. And indeed, Grandma Vandenbergh's Dutch cookbook has a whole chapter on potatoes, which includes about two dozen recipes. In the introductory paragraphs of this chapter, Martine Wittop Koning compares the nutritional value and cost -- as a typically frugal Dutch woman! -- of potatoes and rice. According to her analysis, the proportions of of starch and protein of the cooked foods are roughly comparable, although rice contains a trace amount of fat, whereas the potato has no fat.

Wittop Koning thus suggests adding a small amount of protein in the form of beans or bacon to a meal based on potatoes, in order to make it a more balanced meal and to ensure that care be taken to consume sufficient protein. The recipes in the chapter include boiled potatoes, steamed potatoes, mashed potatoes, roasted potatoes, baked potatoes, and another whole section on how to reinvent leftover potatoes. I chose one of the latter recipes, potato croquettes with ham:

Aardappelcroquetjes met Ham

- 2 1/2 cups cooked potatoes

- 1/2 cup ham, chopped

- 1 egg (optional)

- 1 1/2 tablespoon butter

- 1/3 cup milk

- 1 tablespoon chopped parsley

- salt, pepper, nutmeg to taste

- bread crumbs

- cooking oil (I used non-stick cooking spray)

Make a stiff puree with the potatoes, milk, butter, salt, pepper, nutmeg and chopped parsley.

Mix in the chopped ham with a fork.

Form patties similar to hamburger patties.

Dip the patties in the bread crumbs and fry in hot fat.

Drain on paper towels as necessary, and serve hot.

I found that adding a bit of chopped onion also enhanced the flavor. If you use cooking spray instead of frying in a lot of oil, your croquettes will be lower in fat, and you won't need to drain on paper towels.

The dish is a tasty and economical way to use up leftover potatoes.

Eet smakelijk! Enjoy your meal!

|

| Vincent Van Gogh - De Aardappeleters 1885 |

According to the Netherlands Potato Consultative Foundation, about a quarter of all arable land in the Netherlands is used for growing potatoes; and some 20 percent of this (35,000 to 40,000 hectares) is used for the production of seed potatoes. The majority of the seed crop is exported to over 80 countries around the world. This amounts to an annual export of some 700,000 metric tons of seed potatoes.

The Foundation conducts ongoing research to develop new varieties of potatoes by crossing two strains that exhibit desirable characteristics. The qualities sought by growers include resistance to disease in order to reduce the need for pesticides, the amount of water required to irrigate the crop, and the length of time the harvested crop can be stored.

Every year, the researchers produce over 1.5 million seedlings, but only three or four possible new varieties will be grown for mass production. Once a viable new variety is developed, it has to be quickly multiplied. Large-scale propagation will turn the myriad small plants into hundreds of thousands of salable products, which amount to about 70 percent of the registered world trade in certified seed potatoes.

Based on all of the above, you might suppose that the Dutch have also figured out a variety of ways to prepare potatoes. And indeed, Grandma Vandenbergh's Dutch cookbook has a whole chapter on potatoes, which includes about two dozen recipes. In the introductory paragraphs of this chapter, Martine Wittop Koning compares the nutritional value and cost -- as a typically frugal Dutch woman! -- of potatoes and rice. According to her analysis, the proportions of of starch and protein of the cooked foods are roughly comparable, although rice contains a trace amount of fat, whereas the potato has no fat.

Wittop Koning thus suggests adding a small amount of protein in the form of beans or bacon to a meal based on potatoes, in order to make it a more balanced meal and to ensure that care be taken to consume sufficient protein. The recipes in the chapter include boiled potatoes, steamed potatoes, mashed potatoes, roasted potatoes, baked potatoes, and another whole section on how to reinvent leftover potatoes. I chose one of the latter recipes, potato croquettes with ham:

Aardappelcroquetjes met Ham

- 2 1/2 cups cooked potatoes

- 1/2 cup ham, chopped

- 1 egg (optional)

- 1 1/2 tablespoon butter

- 1/3 cup milk

- 1 tablespoon chopped parsley

- salt, pepper, nutmeg to taste

- bread crumbs

- cooking oil (I used non-stick cooking spray)

Make a stiff puree with the potatoes, milk, butter, salt, pepper, nutmeg and chopped parsley.

Mix in the chopped ham with a fork.

Form patties similar to hamburger patties.

Dip the patties in the bread crumbs and fry in hot fat.

Drain on paper towels as necessary, and serve hot.

I found that adding a bit of chopped onion also enhanced the flavor. If you use cooking spray instead of frying in a lot of oil, your croquettes will be lower in fat, and you won't need to drain on paper towels.

|

| Aardappelcroquetjes met ham |

The dish is a tasty and economical way to use up leftover potatoes.

Eet smakelijk! Enjoy your meal!

Sunday, March 6, 2011

"Potatoes Have Eyes. . .

But they cannot see!" I remember pounding out this song about potatoes when I took piano lessons many years ago. Yes -- the "eyes" of a potato are not for seeing, but are rather a means of vegetative propagation. If you cut up a potato so that each chunk has an eye or two and plant the chunks in the ground, they will each sprout and eventually produce a new plant that is a clone of the parent.

I learned a lot about potatoes when I attended a presentation last week at the New York State Museum. Dr. Roland Kays, a scientist at the Museum, and Chef David Britton of The Food Network collaborated on presenting an entertaining and informative session complete with free food samples. Much of the information they presented was drawn from a fascinating book, Potato: A History of the Propitious Esculent, by John Reader.

Potatoes were first domesticated in the Andes 7,000 to 10,000 years ago, in what is now modern-day Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. There is still a great diversity of potatoes in that area -- over 400 varieties.

The starchy tubers apparently found their way to Europe on Spanish ships as early as 1567. One of the earliest written indications of their presence in Spain is a notation in the records of a hospital in Sevilla in 1573, for the purchase of 19 pounds of potatoes.

This cheap food was quickly adopted by those on the lower rungs of society, due in part to its nutritional value and the ease with which it could be propagated. As a tuber (a fleshy underground plant stem), the potato stores nutrients that help the plant survive long dry or cold seasons. These nutrients also make it an important food source for humans. One medium-sized potato contains about 110 calories, no fat, and also provides a substantial portion of the daily need for Vitamin C, Vitamin B6, and potassium, as well as trace amounts of niacin, thiamin, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, and zinc.

In fact, two to three kilograms of potatoes per day served with a bit of milk, butter, and salt can enable a person to survive for months on this admittedly monotonous diet. The potato became so popular in Europe that by the mid-19th century, millions counted it as the basis of their diet. But since so many of the potatoes cultivated were basically cloned through vegetative propagation, there was very little genetic diversity in the tons of tubers being grown and consumed.

The result was a lack of resistance to disease or blight. That was unfortunate, since when a fungus-like blight attacked the tuber in the mid-1840's, we all know the result: a million people died in the Irish Potato Famine of 1845, and many more who survived left Ireland and emigrated to England, Canada, and the United States.

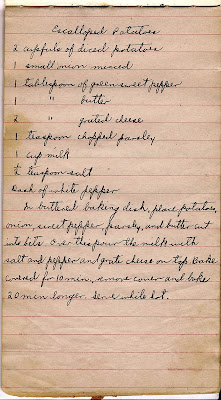

The potato also became an important part of the diet of the Dutch and Germans, including many who also emigrated to the New World. And so the potato found its way to Upstate New York. Both of my cookbooks contain recipes for preparing potatoes. My mother used to make "scalloped potatoes." Grandma Minnie's recipe calls this dish "escalloped potatoes," perhaps an older form closer to the original French from whence the word came. As you might guess, the word is related to "scallop," and refers to cutting meat -- or potatoes in this case -- into thin slices like shells -- scallop shells, of course.

This recipe actually calls for diced potatoes, not thin slices like shells. But notice the milk, butter (and a bit of grated cheese), which not only make the dish tasty, but hearken back to the peasant diet mentioned earlier. Here the simple dish is dressed up a bit by adding onion, green pepper (I added red too for color!), and parsley.

The recipe calls for diced potatoes, not thin slices as my mother used to do. But maybe I cut the "dice" too large, more like ice cubes than dice. So they didn't cook thoroughly at 325 - 350 F. in 30 minutes as the time suggested on the page. I had to stick the dish in the microwave for an additional five minutes.

It had a good flavor anyway, so good in fact that we almost "licked the platter clean," although I doubled the amount of potatoes called for. . . And although my husband almost always adds salt to anything I cook and my son always adds pepper, I didn't add a thing, and I cleaned my plate!

I learned a lot about potatoes when I attended a presentation last week at the New York State Museum. Dr. Roland Kays, a scientist at the Museum, and Chef David Britton of The Food Network collaborated on presenting an entertaining and informative session complete with free food samples. Much of the information they presented was drawn from a fascinating book, Potato: A History of the Propitious Esculent, by John Reader.

|

| Varieties of potato |

The starchy tubers apparently found their way to Europe on Spanish ships as early as 1567. One of the earliest written indications of their presence in Spain is a notation in the records of a hospital in Sevilla in 1573, for the purchase of 19 pounds of potatoes.

This cheap food was quickly adopted by those on the lower rungs of society, due in part to its nutritional value and the ease with which it could be propagated. As a tuber (a fleshy underground plant stem), the potato stores nutrients that help the plant survive long dry or cold seasons. These nutrients also make it an important food source for humans. One medium-sized potato contains about 110 calories, no fat, and also provides a substantial portion of the daily need for Vitamin C, Vitamin B6, and potassium, as well as trace amounts of niacin, thiamin, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, and zinc.

In fact, two to three kilograms of potatoes per day served with a bit of milk, butter, and salt can enable a person to survive for months on this admittedly monotonous diet. The potato became so popular in Europe that by the mid-19th century, millions counted it as the basis of their diet. But since so many of the potatoes cultivated were basically cloned through vegetative propagation, there was very little genetic diversity in the tons of tubers being grown and consumed.

|

| Potato ruined by blight |

The potato also became an important part of the diet of the Dutch and Germans, including many who also emigrated to the New World. And so the potato found its way to Upstate New York. Both of my cookbooks contain recipes for preparing potatoes. My mother used to make "scalloped potatoes." Grandma Minnie's recipe calls this dish "escalloped potatoes," perhaps an older form closer to the original French from whence the word came. As you might guess, the word is related to "scallop," and refers to cutting meat -- or potatoes in this case -- into thin slices like shells -- scallop shells, of course.

This recipe actually calls for diced potatoes, not thin slices like shells. But notice the milk, butter (and a bit of grated cheese), which not only make the dish tasty, but hearken back to the peasant diet mentioned earlier. Here the simple dish is dressed up a bit by adding onion, green pepper (I added red too for color!), and parsley.

The recipe calls for diced potatoes, not thin slices as my mother used to do. But maybe I cut the "dice" too large, more like ice cubes than dice. So they didn't cook thoroughly at 325 - 350 F. in 30 minutes as the time suggested on the page. I had to stick the dish in the microwave for an additional five minutes.

It had a good flavor anyway, so good in fact that we almost "licked the platter clean," although I doubled the amount of potatoes called for. . . And although my husband almost always adds salt to anything I cook and my son always adds pepper, I didn't add a thing, and I cleaned my plate!

|

| Escalloped Potatoes |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)